When is it done? An opportunity to help managers manage

Many developers will have heard a manager ask "when is it done?" and have felt a combination of irritation and dread.

Irritation, because everyone knows the only accurate estimation you can give for most tasks in software development is when it’s actually done. Also, there are many things that are unknowable upfront, so posing the question is a sign of a fundamental misappreciation of what software development entails, which is not the basis of a healthy relationship with your manager.

Dread, because you know that manager wants an answer regardless. Estimate too short, and you’ll have to work overtime or face derision when the time comes. Estimate too far, and you’ll risk not getting the budget at all, or having to do more up-front analyis to see what you can drop. Refuse, and someone else will make the estimate for you and still hold you accountable. There’s a more passive form of refusal: demand exact specifications as a prerequisite of any estimation of work, knowing full well that the business rarely has that in order, meaning you too should be let off the hook.

I propose a more viable way of dealing with the question.

First off: "when is it done?" is usually not the question that a manager should be asking the developer, but it is the question they need to answer themselves. In order to formulate an accurate answer, they need to get a grip on the process of getting it done, of the factors involved. And that’s where you, the software developer, can lend a helping hand.

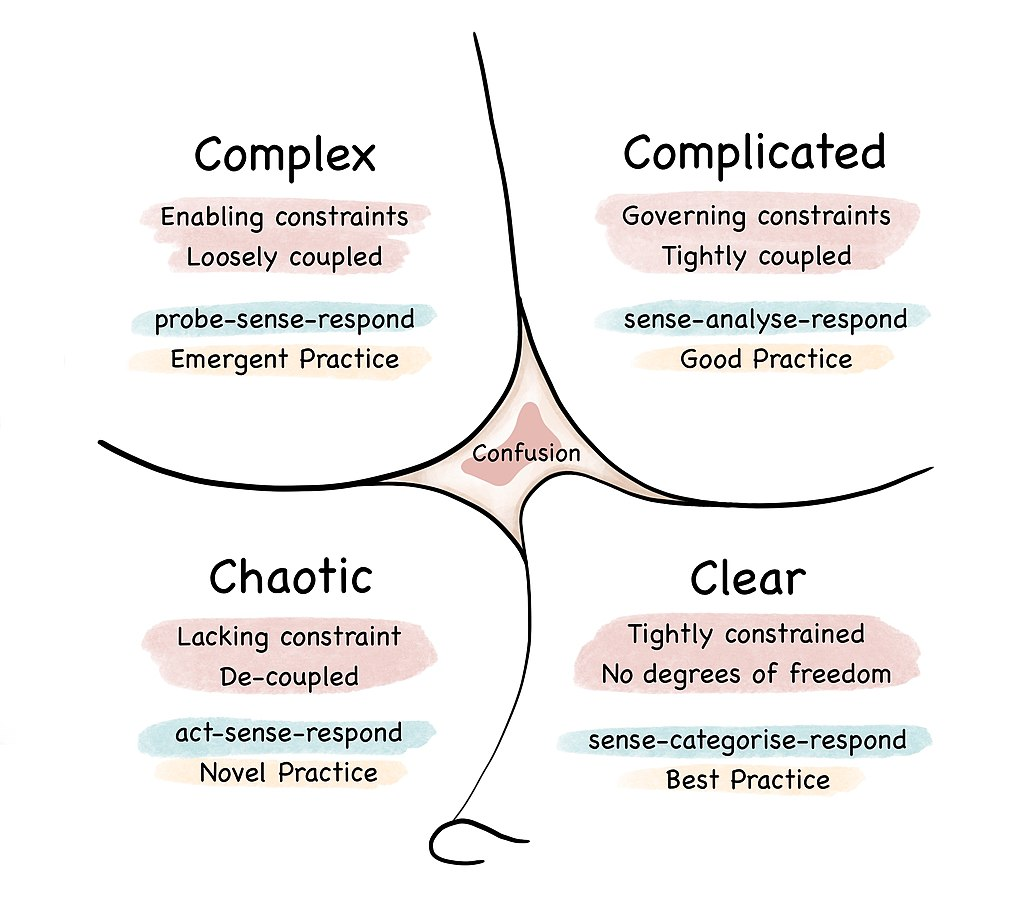

Secondly, I like to point to the Cynefin sensemaking framework for determining the nature of the problem domain and applying the proper mode of problem solving to it. A simple reference image can be found below. A bigger, more overwhelming image of Cynefin, can be found on the wikipedia page. It contains a good few pointers as to what being in the various problem domains entails, but for the point of this article the simple image should suffice.

Waterfall is something you apply in the Simple or Complicated domain, where standard problems are solved with good or standard practices. The problem is clear and static, and the solution is well known. You hire experts that can apply the solution. It’s somewhat predictable. But there’s a reason we stopped doing waterfall-based software development in most of the world: we all know the wishes, requirements, specifications and dependencies are never clear from the start of a software development project. And even when we think they are, they change before we’re done. This is where the endless projects used to come from, that would eat money and produce unfinished or abandoned results. That’s because we’re often in the complex domain, where experimentation and feedback loops are required to discover the path forward. And unless your manager misjudged the complexity of their problems completely and hired you as a tool-expert for a problem that isn’t necessarily solvable with that tool, they will know that your expertise is in probing, sensing and responding with solutions as problems become more clear. It’s why agile software development is still so popular.

And it’s where the irritation may come from: a manager asking when it’s done sounds like they’re assuming the problems, and thus your work, is simple, when it’s not.

But before succumbing to irritation and dread, let’s assume that managers know what they’re doing. We should look at the question as a call for help, and an opportunity to explain the challenges you face in the probing, sensing and responding bit.

For example: - In order to know that your solution is correct, you need feedback from the customer. They should be available, they should know the domain, they should have a mandate to accept or deny the solution. - In order to build, test and deploy the solution, you need CI/CD provisions so that changes can be iterated on quickly. - In order to integrate the solution, you need to align with other developers involved with adjacent systems in the domain. Their plans should align with yours. - In order to comply with regulations and technical requirements, you need to have access to them. And you need someone with the expertise to help you apply them properly. - In order to anticipate on coming work, you need to know to at least some degree what the scope of the work ahead is. Not all the details, but enough to know that when the time comes to pick it up, its dependencies can be met.

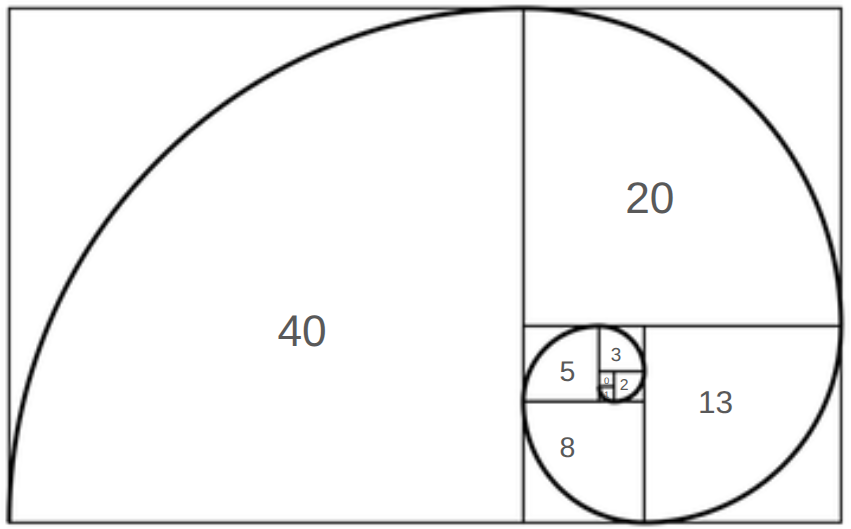

If you’re in a planning poker session, any of the above being unclear or unreliable would be a reason to increase the uncertainty element of your estimate. It’s one reason why the Fibonacci sequence is often used to express the estimation leaps in bigger tasks: missing knowledge, unmanaged dependencies and long feedback loops are what make it hard to predict progress. The answer is in that last sentence: unmanaged.

Noise management

We often feel like these things are noise that prevent us from formulating an answer. But when a manager wants you to help them answer the question "when is it done?", that noise is the answer. That’s what needs to be managed. You can help your manager help you by telling them what they can manage to mitigate uncertainties and risks. It’s in their job title. Now they know what they need to do, to get a better grip on progress. When your progress becomes manageable and your results (sprint review, demo, report, Jira, spreadsheets, etc) visible, anyone who sees the results can extrapolate an answer. Everybody’s happy.