Domain Driven Design - What's in a name? That which we call a rose may not be a rose.

Early on in their career, most software developers develop a muscle memory for writing efficient code and avoiding code duplication. It’s unfortunate that in modular architectures, this practice can seep through into data modelling without context awareness, leading to tight coupling and constraining the software’s ability to be changed.

Things that change together should be together, says the Single Responsibility Principle, which constitutes the S in the SOLID acronym. Consequently, the modules of a modular architecture by definition should exist separately because the functional requirements underpinning their implementation may change independently. A way of achieving this is for modules to follow the Unix philosophy of "do one thing, and do it well". And many developers working with a microservices architecture follow the practice of giving separate applications separate database schemas, or even separate databases entirely that best fit their data model. This way, one application may store the data it "owns" in a way that is isolated from others. Despite these good practices, something dangerous tends to happen when developers, who work in different functional domains, talk to each other about this data.

Domain Driven Design

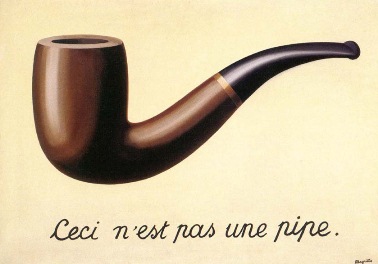

Anyone who has read even the smallest amount on the topic of Domain Driven Design (DDD) will have come across the concept of a Ubiquitous Language. This is an important aspect of DDD: it encapsulates the importance of ascertaining what exact words matter in the field where you’re trying to describe the problem and shape an appropriate solution. When using techniques such as Big Picture Event Storming, ubiquitous language emerges. It becomes clearer which things happen (events) and what things they happen to (entities). One very valuable insight to gain as the flow of events is told and retold, is that a thing with one name can actually be different things, when you start reasoning about its state of existence through that flow.

Let’s take a look at some usecases of a thing not being a thing.

Ticket

For example: Is a ticket to see a film in a cinema always the same thing? You may be thinking of a paper cinema ticket that you show at the door of the theater.

But before you’ve bought it, it’s also called a ticket, yet it’s not in your possession and may even not have been printed. Maybe you’ve booked a ticket but didn’t get a physical copy yet. And maybe you got a ticket for speeding on your way to the cinema.

In the latter case, we generally say "speeding ticket" to denote the difference with a ticket to see the show. That difference is a difference of domain: you driving your car on the road is clearly a different domain than the ticket you need to access the theater.

But when you try to build software for the business processes of someone getting access to a film at a theater, you’ll find that there are various processes with their own domains. The software you build for purchasing a ticket does not care whether you decided to print out a physical copy, or whether it was reserved or not. But as long as we refer to this thing as simply a ticket, we cannot say which exact properties it has or hasn’t. A software developer implementing the payment module only needs to know price and unique identifier, but the developer building the reservation system needs to know what seat, room, date and time the ticket pertains to. The danger lies in these developers talking to various people in the theater business, hearing the word ticket with these various properties, and incorporating all of them into their own data models of a ticket. Suddenly the payment module knows about seats and dates. Before you know it, if the theater decides to change the colour of the physical tickets, the payment system needs an update!

It turns out, that while it’s easy to imagine that a ticket for payment is not a speeding ticket, it’s less obvious that it also isn’t a physical ticket for admission. By using the generic word without considering its context, our urge for deduplication kicks in and we - not just developers - lump those properties together in our brains and consequently in our software solutions.

It may even feel like we’re being efficient, but we can be sure that any change in any part of the theater business processes that have to do with tickets will require a change of all the software. In other words, we will have built a tightly coupled system with a high chance of regression in logically unrelated parts, making continued development quite inefficient. Had we picked names for our ticket that reflected its boundaries in the business processes, for example PayableTicket, PrintableTicket and AdmissionTicket, it would have been immediately clear that these should be separate entities with their own separate entity integrity and some form of referential integrity between them.

This may seem like a no-brainer, but modeling mistakes like this are more prevalent than people realize.

Customer

Another example. Imagine a developer coming into an organization and joining a team that needs to store customer information for anyone who has contacted the company via the website to ask a question.

It may be sufficient to identify this customer via a phone number or email address, in order to send them the requested information. Now imagine this developer attends a meeting with representatives from the finance team and the shipping team and hears them talk about a customer and hearing "it’s crucial that every customer fills in their bank account" and "we cannot have customers in our database with empty address fields; these are mandatory." These are requirements that now surround the concept of a customer. Without knowing that a FinanceCustomer is not a ShippingCustomer, CheckoutCustomer, NewsletterCustomer or SupportCustomer, to name but a few examples, a developer may introduce these fields into their own customer data model.

It gets worse: it not just developers who are prone to making this mistake of optimizing concepts into tightly coupled data models. Business representatives may hear a set of requirements for a concept they recognize and insist their own requirements should be met as well. And even if they don’t, they may be convinced by a developer or product owner explaining that their customer data object needs those extra fields because of requirements unknown to them and simply accept it as an inconvenience. Before you know it, a customer can no longer start a chat or request information without having to create an account where they need to fill out their address and bankaccount information. Not to mention that any system implementing a usecase involving a customer may end up with unnecessary information for which it needs to meet GDPR compliance.

This problem occurs with things called Account and Client as well.

Car

Software development is cursed with needing car analogies to explain itself, and this blog is no different.

During an event storming exercise a few years ago, several groups of developers tried to create a solution design for the car selection process for an imaginary company setting up a car rental service. Every group came up with a different design, which is to be expected - all models of reality are wrong, but some are useful, after all. What was striking wasn’t just that. Every team was talking about cars with the real life picture of a car in their head. People had argued over whether the colour was a relevant property to include in the model. They had included properties like weight, size and fuel type. But in every model, the car was simply called a car.

When asked whether it was relevant for the car selection process to offer cars that were not available for rent, something clicked: Not every car is a car relevant for rental. The first solution somebody suggested was a bad one, but one that is often a red flag for missing a domain boundary indicative of a thing not being a thing: "let’s give the car a flag to indicate whether or not it’s available or not!" How would that work with the next domainspecific usecase popping up where only some types of cars are relevant?

More flags?

public record Car(

String colour,

String brand,

boolean isAvailableForRent,

boolean isAvailableForSale,

boolean isUnderRepair,

boolean isCharacterInCartoon

) {}It would become a tangled, tightly coupled mess. What we needed was an UnrentedCar, or an AvailableCar. It felt so unnatural because we tried to simplify and remove duplication.

The point here is not whether these suggested names are the best solution or not, or whether you should use object inheritance in the implementation. But writing out AvailableCar in your code and/or documentation, or CarForRent, or even CarThatIsAvailableForRent, doesn’t cost anything and carries enough expressiveness to clarify a distinction with other business processes involving cars.

Leaving out descriptive information in the words used to describe concepts for the sake of efficiency is an error that blurs domain boundaries and opens the door for tight coupling.

Product

The abovementioned examples involved similarly named objects in different contexts, but the same issue exists for individual properties of those objects.

At an e-commerce company where I worked, everything revolved around selling products. For a time, a new initiative was plagued with difficulties trying to procure a product throughout the chain of microservices that were involved with the business process.

During one alignment meeting, developers and analysts from the four teams involved with product information, product stock, promotion and checkout were confident that they should converge on using the "productId" to ensure every system would be able to reference the same product throughout the business flow. As we were about to close the meeting on the conviction that we were in agreement, on a hunch, I decided to ask what exactly "product id" meant for everyone. The result was shocking.

-

The people from product information thought everyone was talking about EAN.

-

The folks from product stock had SKU in mind.

-

Promotion actually had a field called productId in their datamodel, but it was a legacy field that turned out to have a format that seemed to match the productname field of the checkout team.

-

The checkout team had all those fields and had implemented a method that would simply try all of them to try when finding a match.

We were aligned on a word, but not on its meaning, because we hadn’t gone through the due diligence of defining it together with its proper context.

Conclusion

-

Duplication is a problem regularly observed in microservices, but isn’t necessarily a violation of the single responsibility principle. It may be erroneous omission of explicit context.

-

Give things specific names; saving characters by avoiding longer object- and fieldnames does not save you money but costs you expressiveness.

-

This isn’t just a challenge of software. If you have to use a generic name for a thing, mention its specific domain any time you talk with someone beyond the boundaries of your domain - that includes in documentation.

To end with a famous quote:

What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet

Sharespeare in Romeo & Juliet

or to paraphrase:

That which we call a rose may be an insufficiently distinctly described thing that exists among different namesakes in other rose-related domains that have no discernable scent at all.

just now in this article