A first look at GitHub Codespaces

Join me for my first look into GitHub Codespaces. I’ll walk you through setting up some basic configuration, and some things to keep in mind.

Join me for my first look into GitHub Codespaces. I’ll walk you through setting up some basic configuration, and some things to keep in mind.

The is macro in the clojure.test namespace can be used to write assertions about the code we want to test. Usually we provide a predicate function as argument to the is macro. The prediction function will call our code under test and return a boolean value. If the value is true the assertion passes, if it is false the assertion fails. But we can also provide a custom assertion function to the is macro. In the clojure.test package there are already some customer assertions like thrown? and instance?. The assertions are implemented by defining a method for the assert-expr multimethod that is used by the is macro. The assert-expr multimethod is defined in the clojure.test namespace. In our own code base we can define new methods for the assert-expr multimethod and provide our own custom assertions. This can be useful to make tests more readable and we can use a language in our tests that is close to the domain or naming we use in our code.

The clojure.test namespace has the are macro that allows us to combine multiple test cases for the code we want to test, without having to write multiple assertions. We can provide multiple values for a function we want to test together with the expected values. Then then macro will expand this to multiple expressions with the is macro where the real assertion happens. Besides providing the data we must also provide the predicate where we assert our code under test. There is a downside of the are macro and that is that in case of assertion failures the line numbers in the error message could be off.

The namespace clojure.pprint has some useful function to pretty print different data structures. The function print-table is particularly useful for printing a collection of maps, where each map represents a row in the table, and the keys of the maps represent the column headers. The print-table function accepts the collection as argument and prints the table to the console (or any writer that is bound to the *out* var). We can also pass a vector with the keys we want to include in the table. Only the keys we specify are in the output. The order of the keys in the vector we pass as argument is also preserved in the generated output.

Recently, I stumbled upon a revelation that seems to echo across organisations in various industries: in the final stages of longstanding contracts, a sudden misalignment emerges between the products or services offered and the current market demands.

This discovery wasn’t entirely unexpected, given my Wardley Mapping experiences. But how does this insight translate into action for us, both individually and as a company?

As architects, especially in the area of consulting and secondment, it is important to continually evolve. Clients don’t just seek relevant expertise, but also continually added value from external partners. What do we as consultant-architects do, to keep an eye on our ‘continuity’ over time? How do we ensure that we remain at the forefront of innovation, rather than becoming outdated relics of the past?

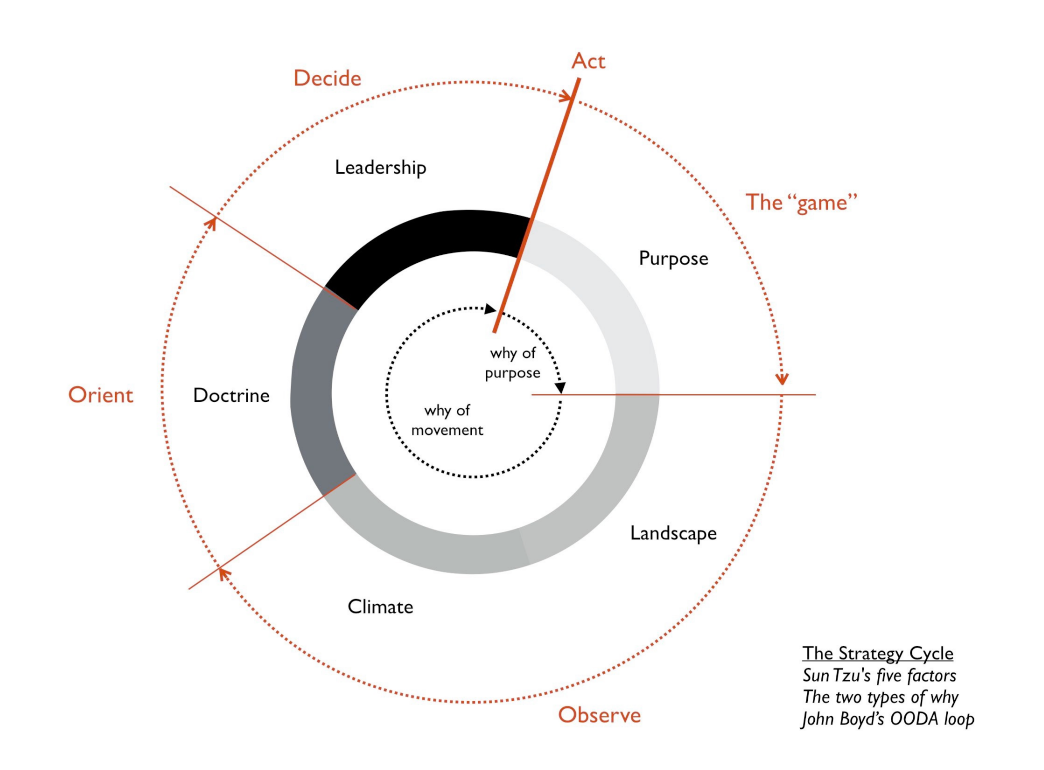

This blog post describes my personal journey in which I will delve into my strategic approach to remaining relevant in our industry, using Wardley’s strategy cycle as my guiding compass:

As promised last time, in the third and final installment we would look at some actual code. As it will turn out, our straightforward implementation will need a little rework in order to properly fire up the GPU.

When we mock a method that returns a Stream we need to make sure we return a fresh Stream on each invocation to support multiple calls to the mocked method. If we don’t do that, the stream will be closed after the first call and subsequent calls will throw exceptions. We can chain multiple thenReturn calls to return a fresh Stream each time the mocked method is invoked. Or we can use multiple arguments with the thenReturn method, where each argument is returned based on the number of times the mocked method is invoked. So on the first invocation the first argument is returned, on second invocation the second argument and so on. This works when we know the exact number of invocations in advance. But if we want to be more flexible and want to support any number of invocations, then we can use thenAnswer method. This method needs an Answer implementation that returns a value on each invocation. The Answer interface is a functional interface with only one method that needs to be implemented. We can rely on a function call to implement the Answer interface where the function gets a InvocationOnMock object as parameter and returns a value. As the function is called each time the mocked method is invoked, we can return a Stream that will be new each time.

This is our first blog in a series where we interview our consultants about their projects, current challenges, and how they approach these challenges. We build up the story in three parts: first, we sketch the context in which the project takes place; next, we look at the assignment and responsibilities. Finally, we dive into the approach taken and lessons learned by the consultant. In this first episode, we interview Aino Andriessen, IT-Architect.

Sometimes the answer to your problems is right in front of you. But somehow you just can’t grasp it until you’ve had a bit of an enlightenment experience. This happened to me a couple of weeks ago.

A Gradle build file describes what is needed to build our Java project. We apply one or more plugins, configure the plugins, declare dependencies and create and configure tasks. We have a lot of freedom to organize the build file as Gradle doesn’t really care. So to create maintainable Gradle build files we need to organize our build files and follow some conventions. In this post we focus on organizing the tasks and see if we can find a good way to do this.

It is good to have a single place where all the tasks are created and configured, instead of having all the logic scattered all over the build file. The TaskContainer is a good place to put all the tasks. To access the TaskContainer we can use the tasks property on the Project object. Within the scope of the tasks block we can create and configure tasks. Now we have a single place where all the tasks are created and configured. This makes it easier to find the tasks in our project as we have a single place to look for the tasks.

The IntelliJ HTTP Client is very useful for testing APIs. We can use Javascript to look at the response and write tests with assertions about the response. If an API returns a JSON Web Token (JWT), we can use a Javascript function to decode the token and extract information from it. For example we can then assert that fields of the token have the correct value. There is no built-in support in IntelliJ HTTP Client to decode a JWT, but we can write our own Javascript function to do it. We then use the function in our Javascript response handler to decode the token.

In today’s fast-paced digital world, complex solutions form an all-time high demand on the cognitive capacity of your team. That is why, in this article, we will introduce a rule of thumb for sizing solutions based on what your organization can handle. We will give a short introduction on cognitive load theory and organizational constructs. We believe that architects must consider these while decomposing their solutions into autonomous parts of a system that continuously and incrementally delivers value to the organization.